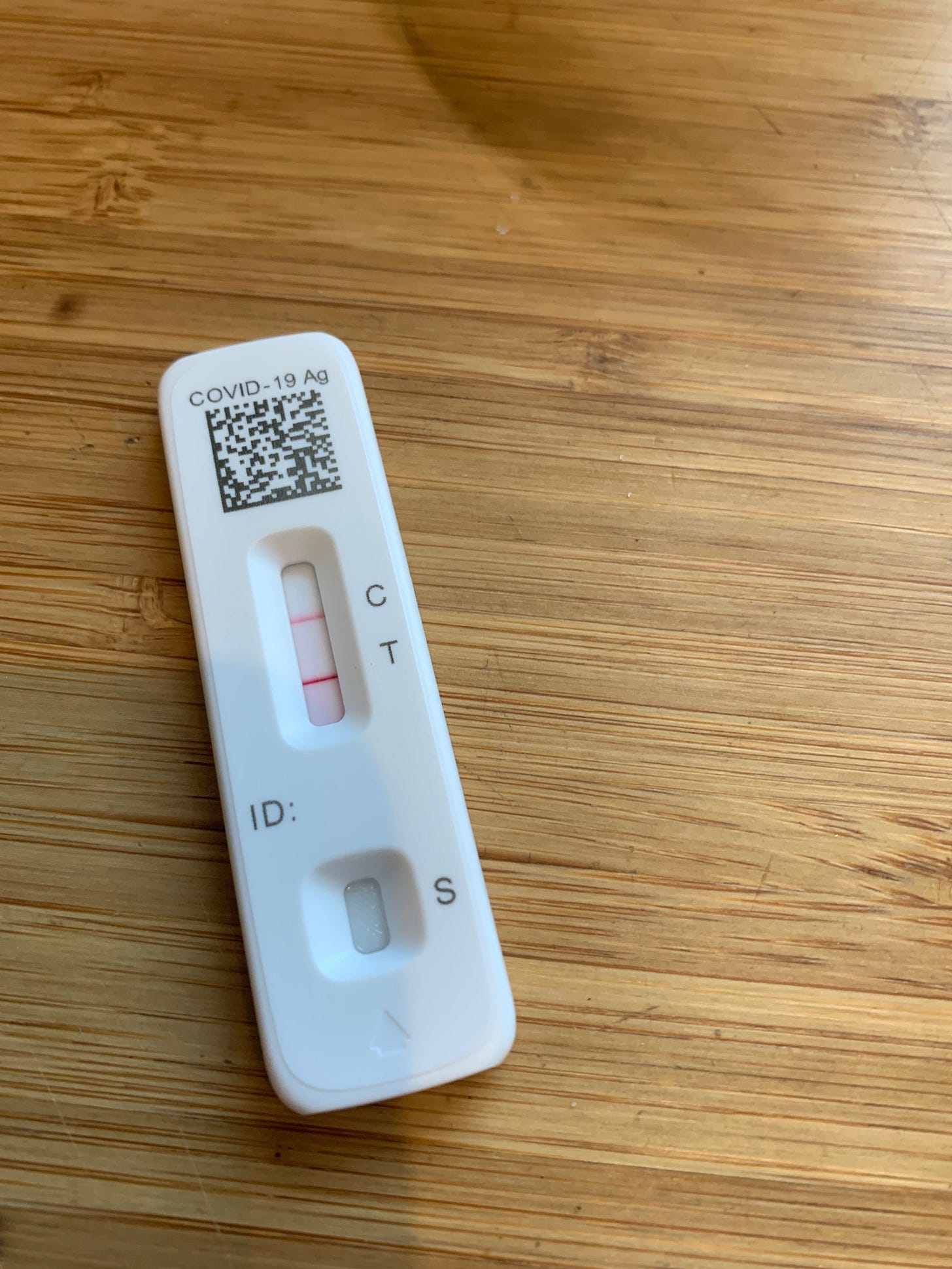

We landed in Lisbon on Friday morning and on Saturday’s train south I started complaining about sinus pain. I’d slept poorly the previous nights — jet lag and an overnight flight where I had to repeatedly stop my daughter from sliding into the footwell or the aisle — and it was very dry in Lisbon. Maybe this was when the jet lag was really catching up, I thought, when Sunday brought disorientation and fatigue. I skipped the beach and napped. When I woke up I felt marginally better, but my skin felt prickly and uncomfortable. I pulled a COVID test off my mother-in-law’s bathroom shelf.

It turned positive immediately.

I’m vaccinated and it’s not my first time catching it, so it’s not terrible; I am holed up in a spare room at my mother-in-law’s apartment in the Algarve, the Southernmost region of Portugal. I wear a KN95 when I leave the room, sleep as much as I can, and bask a little in the sun on the abundant balconies. I’d prefer being well, but this is one of the better places to be ill. The sky is bright blue, I can just see the ocean out my window, and at night the bats flutter around the roofs and treetops. I’m surviving on local cheese that tastes a bit like a barn, and very cured salami, and salad, and chocolate pudding.

Assuming everyone else stays healthy, this shouldn’t derail our trip much. I’m OK to travel (masked, of course) after tomorrow, and our flight to Finland is Thursday. Today I feel better than yesterday, and God willing that trend will continue.

One way in which the US is better than the EU: Paxlovid is much easier to get in the States. We’ve been trying to figure out the logistics in case my mother-in-law gets sick, and it’s just impossible here — unless you’re elderly and unvaccinated, or an organ transplant recipient.

One way in which the EU is better than the US: Rapid tests are 2.50 euros at the Portuguese pharmacy.

We did get to see a little of Lisbon before I took ill. To be annoyingly American: I will declare, on the basis of our 26 hours there, that it is a great city.

Traveling with Rosa means that we pick one or two things we adults want to see each day, and the rest of our time is spent doing normal parent things: going to playgrounds, sourcing snacks, urgently finding public restrooms.

Accordingly, what stands out to us when we travel is the quality of public space. And Lisbon’s was great: Tons of adequate public restrooms, very diverse and friendly populace, pretty good public transportation, plentiful benches, clean and expansive parks. One obvious-in-retrospect genius is that the two playgrounds we went to had snack bars next to them that sold coffee, beer and cocktails, plus quick, friendly meals. It is unbelievably pleasant to eat breakfast and sip a galão latte and let the kid run rampant in the perfect summer weather. Plus the food and coffee are affordable; I’ll miss the €.90 espressos when we get to Finland.

The one thing we picked to see for adults was the Aljube Museum of Resistance and Liberation, housed in a prison the Salazar regime used to incarcerate political prisoners. Antônio Oliveira Salazar’s Estado Novo was the longest-lasting right-wing dictatorship in Europe, and I think is relatively unknown by U.S. Americans; the Wikipedia page for it is shockingly apologetic, and other foundational resources online are hard to find.

So I learned more about it from the recollections and histories of those who resisted it, often at great cost to themselves and their families. As you may expect, it was not child-friendly, so the visit was a little more hurried than I would have liked.

I was most interested in the deep interconnections between Salazar’s dictatorship and the Portuguese colonial war. The Estado Novo was ideologically committed to maintaining its colonial dominance over Asian and African territories in a way that made it uniquely devoted to suppressing independence movements such as Amílcar Cabral’s African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde. In fact, the PIDE secret police were both the primary mechanism of internal repression and of counterinsurgency in the colonies. Thus, resistance in Portuguese civil society to the regime (including from labor, students, and communists) was complemented by the armed independence movements. The Estado Novo was ultimately undone because Africans under Portuguese rule successfully fought back against the empire and Portuguese society grew to oppose these colonial wars. As students fled conscription, lower-ranking military officers instigated a military coup now known as the “Carnation Revolution.” Unlike other overthrows of dictatorships, there were no civil society mass demonstrations preceding this coup; instead, spontaneous, broad civilian involvement afterwards helped to secure the transition to democracy. (It also ended the Portuguese Empire, liberating Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau.)

The Aljube Museum includes substantial exhibits weaving this history together, along with the history of this prison (where political prisoners were tortured and kept in solitary confinement “drawers” barely big enough for a man to lay down). If you want to learn more, their web site has a section that recalls events #inthisday in history. But it’s also a museum with an explicit agenda: To remember history in the service of building a strong democratic polis.

On one stark red wall towards the end of the permanent exhibit, this large slogan is emblazoned: Sem memória não há futuro. “Without memory, there is no future.” Smaller text below reads: “Preserving the Memory of History is an act of Citizenship, breaking the silence in which everyone was submerged and rescuing them in order to educate the younger generations.”

It’s worth a trip, if you are in Lisbon — to learn more about this history and to think about how societies remember this kind of history. This is a cynical and beleaguered age; talk of “citizenship” in the American context is usually done in an effort to exclude immigrants, rather than to invoke the sense of a democratic subject consciously shaping the country’s future. We need these civic aspirations that grow from knowledge of the bloody and bruising authoritarian alternative. I expect that the National Memorial for Peace and Justice has a similar resonance, in the American context; I’d like to go someday.

Send us some well-wishes or prayers if you can — we’ll know in the next couple days if I’ve infected anyone else. Otherwise, I think the next update will be from Finland, where the political rhetoric is looking distressingly familiar…

Shay,

Do you take Vit D? I highly recommend daily vit D-3, and Zinc lozenges. Most people who got COVID were very low in vit D-3. Wishing you a speedy recovery.